“I Didn’t Really Have Your Typical Upbringing. I Mean, I Did at First… but Then the World Ended.” – Joel Dawson

Originally titled; Monster Problems, the Netflix Original, Love and Monsters, released in 2020, is a comedic, post-apocalyptic romance filled with plenty of heart, humour, clever world-building and, as its title suggests, gigantic monsters. Despite housing a few blemishes here and there, Love and Monsters covers an abundance of emotional ground throughout its story, standing as an entertaining, monster-filled adventure, the sort of film that delivers wit, excitement and creativity all in generous portions, making for an amusing time during ‘the end of times,’ as it were.

Plot Summary: Seven years after the world-ending event known as the “Monsterpocalypse,” twenty-three-year-old Joel Dawson, along with the rest of humanity, is wearily living underground in a hidden bunker since colossal mutated monsters took control of the surface. But, after reconnecting over the radio with his high school girlfriend, Aimee, who is now eighty miles away at a coastal colony, Joel courageously decides to venture out into the monstrous open-air to find her…

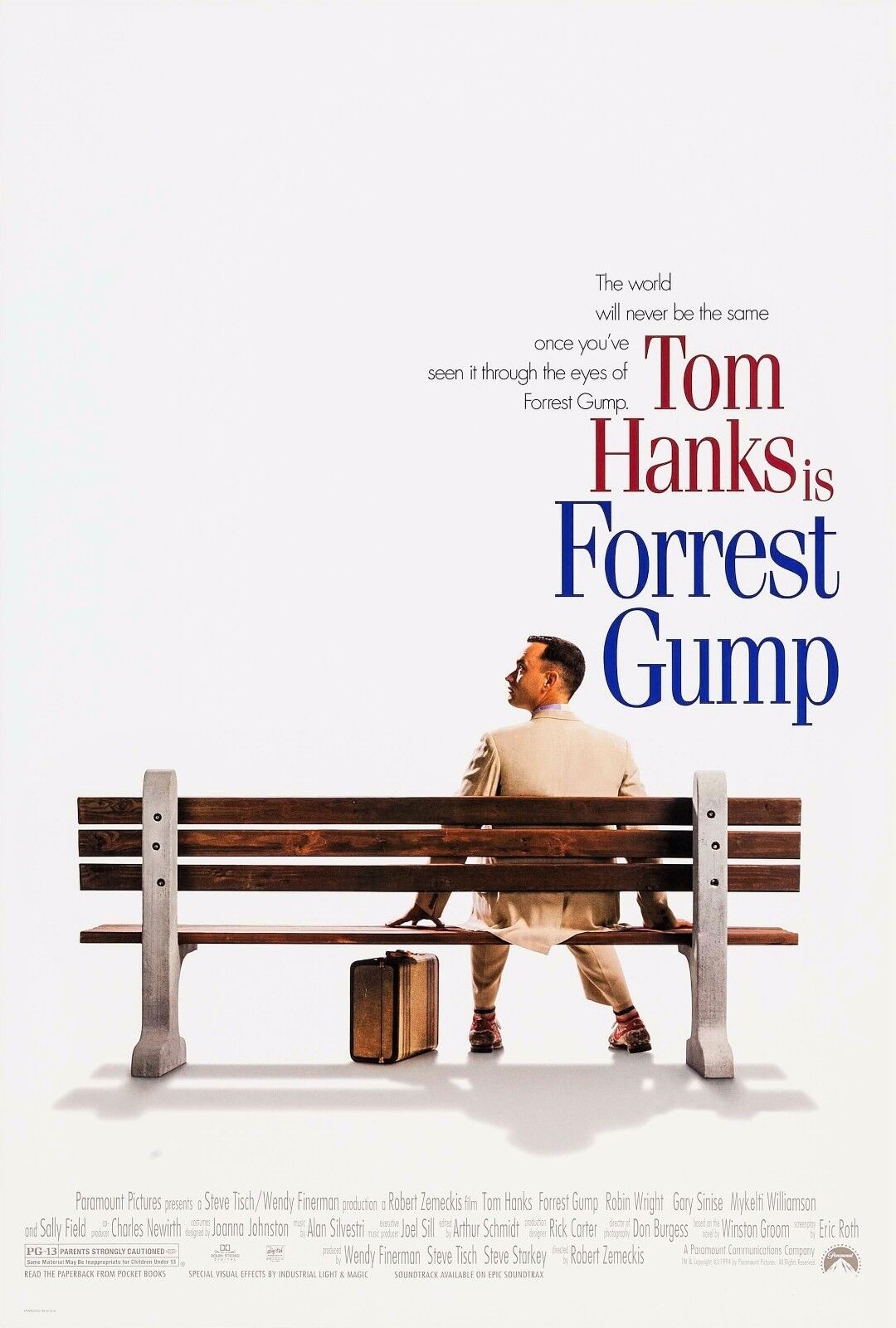

Demonstrating his storytelling capability almost immediately, director Michael Matthews (Five Fingers for Marseilles) artfully lays out the film’s premise during the opening sequence, employing a voiceover from Joel and a variety of animated illustrations made to appear as if they were pencil-sketched by Joel in his notebook. Through this opening, we learn that several years ago, the human race fired a series of rockets into space to destroy an impending asteroid nicknamed; “Agatha 616,” which successfully blew the rock to smithereens. However, this action had consequences, as the chemical compounds used to launch the missiles rained back down to Earth and transformed the cold-blooded wodge of the animal kingdom into mutated monstrosities, forcing the human race to flee underground. From this point on, Love and Monsters continually explores its unique world, building upon the notion of the “Monsterpocalypse” in several ways whilst also taking cues from 2009’s Zombieland by not taking itself too seriously, avoiding the common concern of its post-apocalyptic setting feeling ‘played out.’ Of course, this does mean that Love and Monsters includes a number of tonal shifts, some of which occur rather suddenly, similar to how many of the film’s gags vary in quality.

In terms of characters, the timid, self-deprecating protagonist of Joel Dawson is perfectly cast with Dylan O’Brien, as the screenplay allows the young actor to flex every acting muscle he possesses, toeing the line between weighty and light-hearted scenes through his myriad of interactions with the other survivors of his monster-infested world. For Joel, the world-ending cataclysm was particularly bad timing as he was on a date with his girlfriend Aimee when the pair were separated and shipped to different colonies. While terrified of almost everything at first, Joel eventually pushes himself out of love, serving as a likeable yet dimwitted guide through a world of horrors and devastation, discovering more about himself along the way. In addition to O’Brien, the cast is studded with some great talent, from Jessica Henwick, who manages to make Aimee seem capable and sympathetic in spite of her limited screen-time, to the unlikely pairing of Michael Rooker and Ariana Greenblatt as Clyde and Minnow, two world-weary survivors travelling together after their respective families were killed by undisclosed creatures. Moreover, whilst on his journey, Joel encounters the grieving, intelligent canine, Boy, who is remarkably well-portrayed on-screen by the two Australian kelpies, Hero and Dodge.

Given that much of the film is a voyage across post-apocalyptic America, Love and Monsters is almost episodic in its visual presentation, following Joel as he treks past devastated, overgrown suburbs, corroded fairgrounds and expansive meadows, all of which are wrapped in impressive details like spider-like webbing enfolding the rooftops and trickling egg sacks sprouting on trees. Lachlan Milne’s cinematography and the film’s wonderful production design (considering its modest budget for a premise of this scale) lend themselves brilliantly to this concept with an ample amount of wide shots, thoroughly embracing the strange beauty and vibrant colours of the “Monsterpocalypse.”

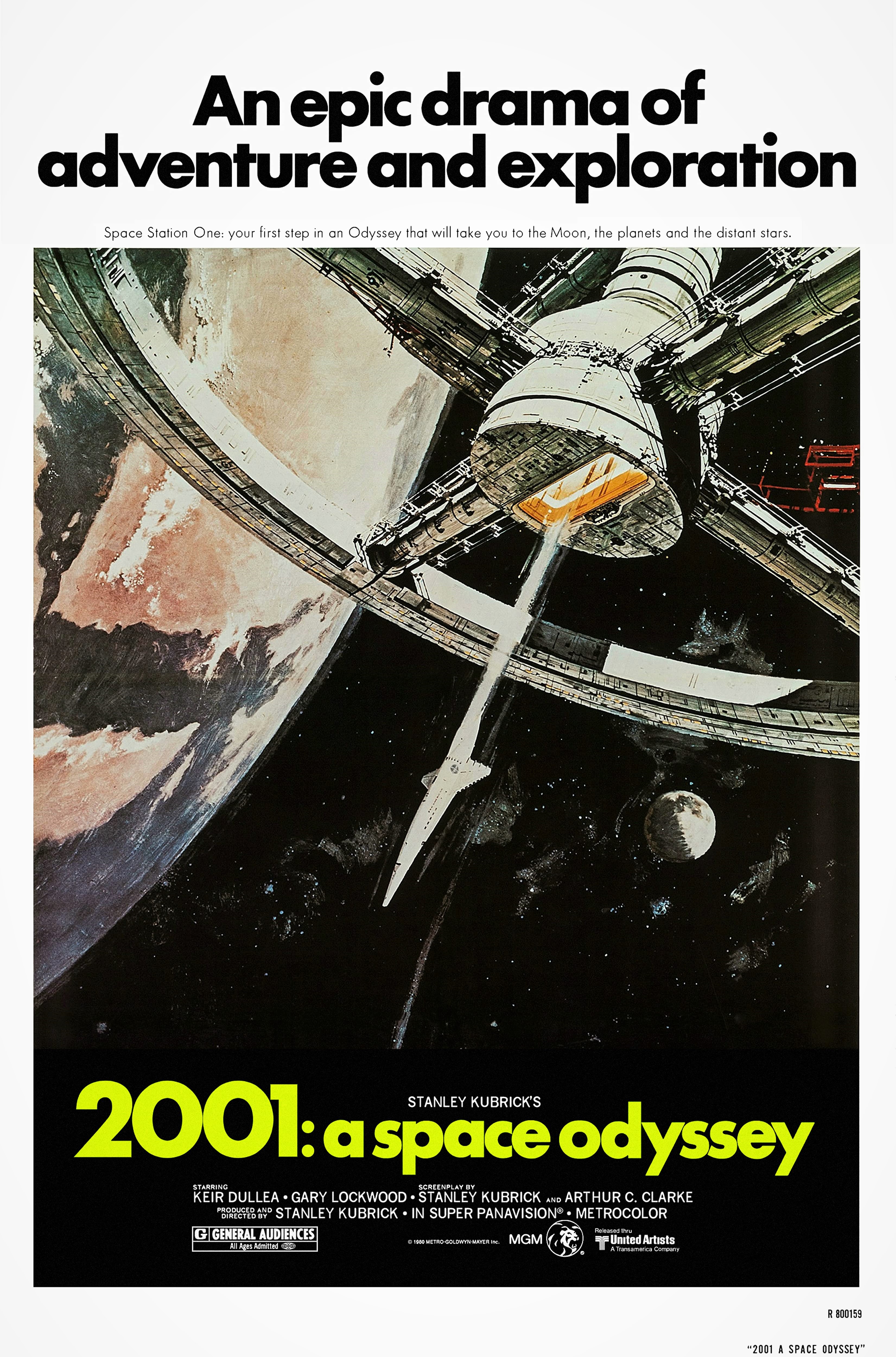

Drawing inspiration from the scores of larger-than-life science fiction classics from the 1950s and 1960s, composers Marco Beltrami and Marcus Trumpp provide Love and Monsters with a grand, stimulating and highly vigorous orchestral score. Through tracks such as; Bunker Breach, Wisdom of the Wild, Amiee’s Colony and End Credits, the original score works in tandem with practically all the scenes it can be heard, whether they are stirring or unsettling.

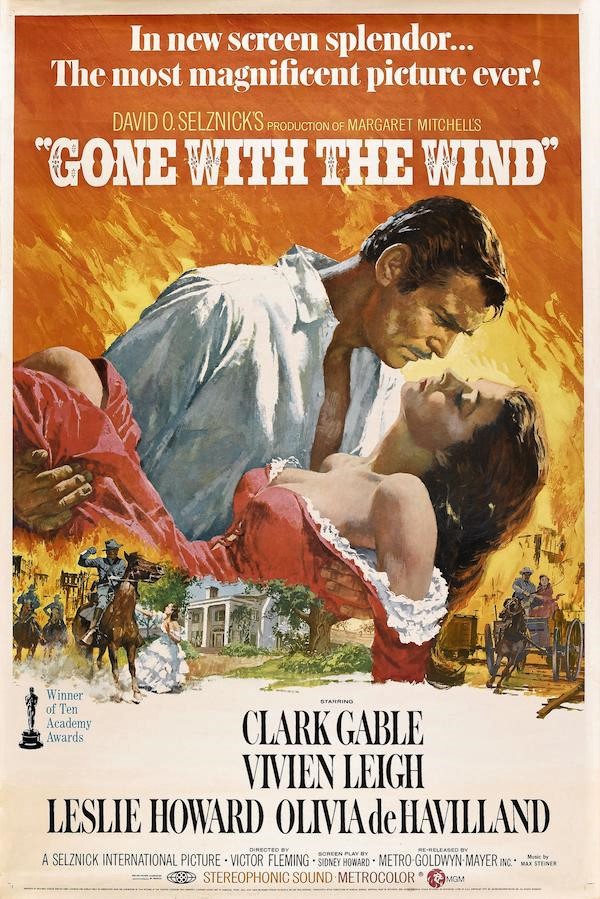

As you’d hope for a monster-centric flick, the titular creatures of Love and Monsters are widely imaginative, with oversized centipedes, frogs, snails and crabs all featured throughout the runtime, all outlandish and intimidating in design, yet still recognisable to their real-world counterparts, brought to life via exquisite practical and CG effects, ultimately leading the film to become an Oscar nominee in 2021’s Best Visual Effects category, alongside Tenet (2021) and The Midnight Sky (2021).

In summary, Love and Monsters is an enjoyable, earnest and comforting flick, packed with splendid creature designs, charming characters and a delightful cast. In many ways, the film is a high school rom-com that just so happens to be set in a post-apocalyptic world, serving as a terrific template for crafting a leaner, less bloated summer flick that virtually all can enjoy. And, for once, with the film leaving things open-ended enough for a sequel, this is the rare scenario where, I’d say, another instalment would actually be welcome. Rating: low 8/10.