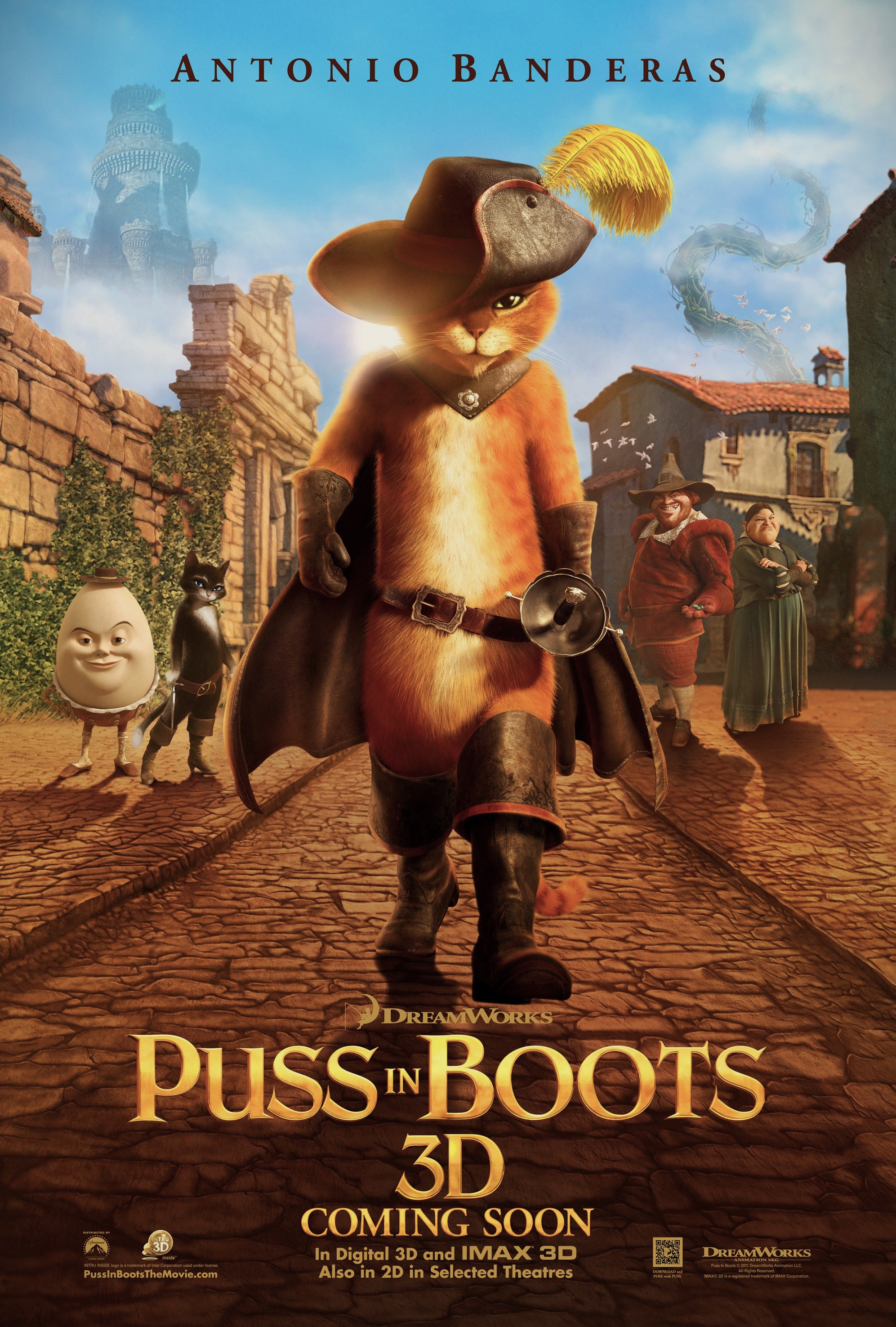

“Fear Me, if You Dare!” – Puss in Boots

Released in 2011, one year after the highly-praised Shrek series supposedly concluded with Shrek Forever After (2010), Puss in Boots acts as a spin-off and prequel to the endearing ogre’s renowned franchise, retaining its emphasis on parodying fairy tales whilst supplying the titular heroic feline with an amusing, stand-alone adventure that frequently pays tribute to Spanish cinema. While not profound in terms of storytelling nor revolutionary in terms of animation, for what it lacks in depth, Puss in Boots, directed by Chris Miller (Shrek the Third), makes up for with an abundance of family-friendly wit and excitement, in spite of the initial plan to turn the film into a mere direct-to-DVD spin-off.

Plot Summary: Long before meeting Shrek and Donkey, the adorable yet cunning vigilante Puss in Boots aimed to clear his name, striving to escape his notoriety as the suspected thief of his hometown, San Ricardo. Then, one faithful night, after overhearing that the murderous outlaws Jack and Jill have come into possession of magic beans, Puss senses a window of opportunity, setting out to steal the beans in pursuit of the treasure they lead to, eventually crossing paths with an old friend…

In contrast to the Shrek films, which were in production for around three years (except for the first, which was in production for almost five), Puss in Boots took over seven years to produce, entering development just after the release of Shrek 2 (2004). The film also differs from the Shrek series in other ways, most notably in its inspirations. Where the Shrek franchise became recognised for its parodying of classic fairy tales and modern pop culture, Puss in Boots is more reminiscent of Spanish cinema, namely, Spanish action and adventure flicks, harbouring references to well-known flicks, like The Mask of Zorro (1998), a film which interestingly, also featured Antonio Banderas as the lead, and Desperado (1995), another release featuring Banderas as well as his co-star Salma Hayek. As such, Puss in Boots operates as a successful mish-mash of ideas, blending elements of fairy tale fantasy with solid action sequences reminiscent of traditional vigilante flicks. The majority of the story, though, is a riff on the famed fable of Jack and the Beanstalk, a fairy tale adapted time and again. Thankfully, the writers were aware of this, implementing a handful of original ideas to form their own take on the well-worn story.

The central cast of Antonio Banderas, Salma Hayek, Zach Galifianakis, Billy Bob Thornton and Amy Sedaris are superb in their vocal performances, with the newly-introduced characters being well-defined and entertaining, from Humpty Dumpty, Puss’ intelligent yet untrustworthy ally, to Jack and Jill, an amusingly fiendish pair of villains, and the skilled thief Kitty Softpaws, who bears a fairly moving backstory. Truly, the only character that lacks interesting characterisation is Puss himself, who is essentially the same character he was in 2004, with little difference in his personality despite being younger, less experienced and more independent, harbouring no major distinctions or a compelling character arc.

For this film, an admirable decision was made to make the world of Puss in Boots appear very different from that depicted in the Shrek series. In the latter, the environments were similar to classic fairy tale illustrations, often featuring extravagant kingdoms and vibrant forests, with even the earliest appearance of Puss in Boots himself being depicted in clean, pencilled illustrations in a vast woodland environment amidst the book; Histories or Tales of Past Times, Told By Mother Goose, written by Italian author Giovanni Francesco Straparola in 1551. However, the film has a distinctly Spanish feel, with most of the runtime being set in deserts and rural towns sporting Colonial architecture, in addition to a warmer, more terracotta colour palette. The animated cinematography and the animation itself also go a long way in enhancing the film’s many action sequences and visual gags, including one set piece with a gigantic creature wreaking havoc, undoubtedly inspired by the Godzilla series.

Capturing the spirit of adventure much like the film at large, the original score by Henry Jackman is rousing, occasionally even harbouring a slight western feel. Furthermore, tracks such as Chasing Tail and Farewell San Ricardo convey Puss’ heroism and vigilante persona flawlessly, whilst Jack and Jill are granted a monstrously malicious melodic cue with the plainly-named track; Jack and Jill. The end credits song; Americano by Lady Gaga, seems rather out-of-place among the rest of the soundtrack, however, given that Puss in Boots never employed contemporary songs in its fantastical setting before this moment, unlike the Shrek franchise.

Humorously, the animators behind Puss in Boots didn’t bring any cats into the studio to study their movements for the various felines that appear throughout the runtime. Instead, they simply watched some of the millions of widespread cat videos on YouTube to make each cat’s movements as lifelike as possible and take inspiration for some of the film’s cat-related antics.

In summary, Puss in Boots is a delightful adventure with enough entertainment value to keep both younger and older audience members engaged, even if the film isn’t as memorable as some of the entries from the series its protagonist originated. Still, it likely goes without saying the film’s late-to-the-party sequel; Puss in Boots: The Last Wish (2022), was an improvement over its predecessor in almost every way. Rating: 6/10.