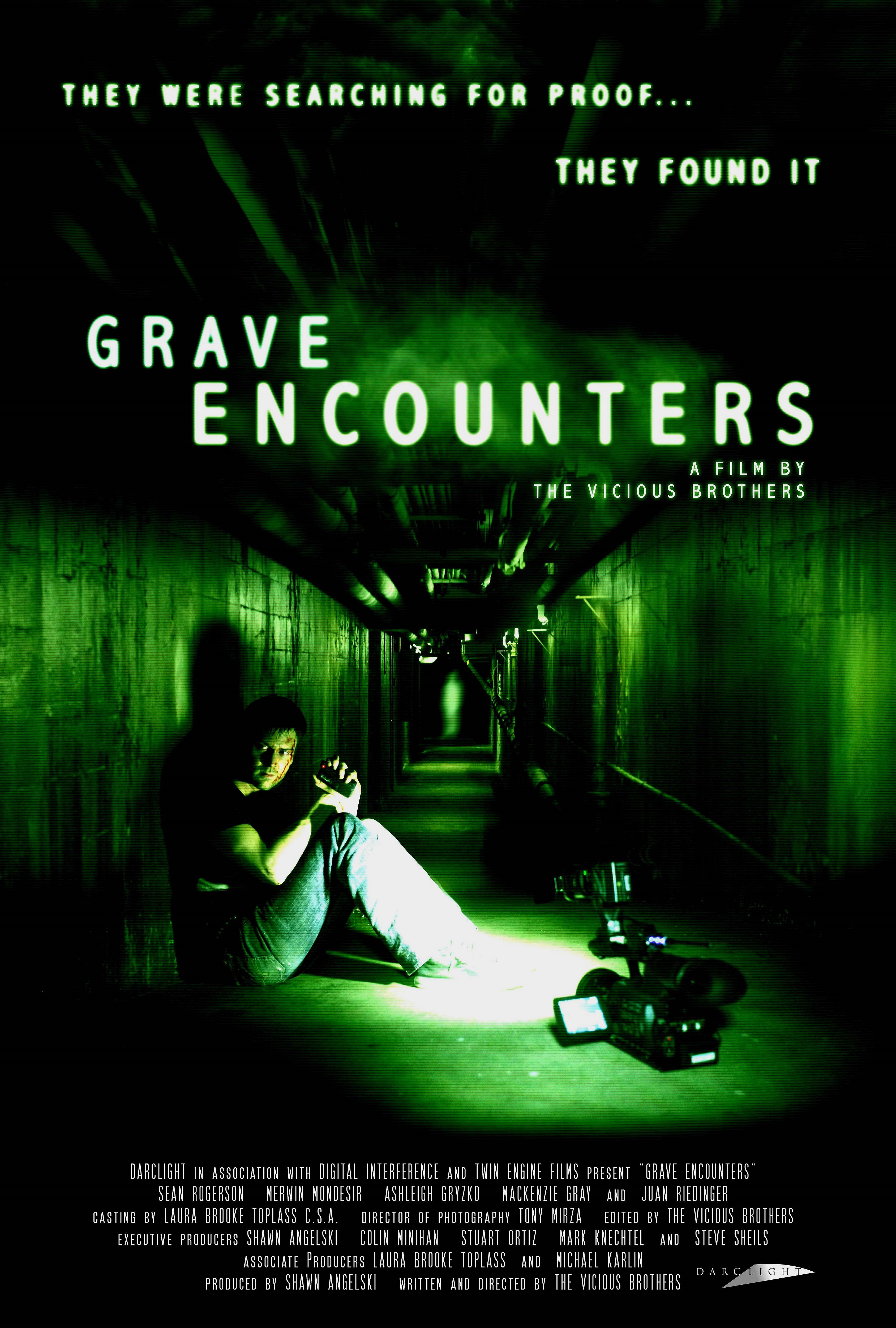

“This Place Is About as Haunted as a Sock Drawer…” – Lance Preston

Impressively produced on a budget of around £89,000, the 2011 found-footage flick; Grave Encounters, is an effective, if rarely groundbreaking, contemporary horror. Whilst not as down-to-earth or as painfully slow-paced as several other found-footage releases, such as Paranormal Activity (2007) or Mr. Jones (2013), Grave Encounters wastes little time getting into the monstrosities that lie within the walls of its central setting of an abandoned psychiatric hospital, utilising its dark corridors and rusted medical equipment to deliver memorably creepy moments and a fairly unnerving atmosphere, despite its many faults.

Plot Summary: Voluntarily locking themselves inside the infamous, abandoned Collingwood Psychiatric Hospital, to increase the stakes of their ghost-hunting reality show, Grave Encounters, host Lance Preston and the rest of his team prepare to capture every minute of their overnight paranormal investigation on camera. But, as the hospital’s walls begin to shift into a labyrinth of endless corridors, each inhabited by the spirits of former staff and patients, the group soon realise they may be filming their last episode…

Written and directed by Colin Minihan and Stuart Ortiz, also known as the “Vicious Brothers,” the format and host of the fictional Grave Encounters reality show takes influence from the real-world series; Ghost Adventures, and its host, Zak Bagans, known for his black muscle t-shirts and technique of attempting to invoke paranormal activity by cursing at the supposed spectres, inviting aggression. This inspiration is evident from the outset, as Grave Encounters humorously mocks the ghost-hunting reality shows of the late 2000s, dissecting the manufactured appeal behind the format and its many tricks of the trade. For example, early on in the film, Lance pays a groundskeeper to provide a false statement during an interview that he witnessed paranormal activity on the grounds of the hospital, a known practice in supernatural reality television, as over the years, hundreds of interviewees have publicly admitted to being paid to “Just Make Something Up for the Camera.”

The central cast of Sean Rogerson, Ashleigh Gryzko, T.C. Gibson, Mackenzie Gray and Juan Riedinger provide the occasional moment of levity early in the runtime as a means to break up the flurry of distress and torment their characters later endure. During many of these moments, the characters also make offhand comments regarding their situation, referencing filmmaking conventions and well-known horror tropes that add a level of realism to the dialogue. This doesn’t mean that all of the Grave Encounters crew are strictly likeable, however, as T.J., the truculent cameraman, does far too much complaining and arguing whilst the host, Lance Preston, and the supposed psychic, James Houston, are suitably sleazy for success-hungry individuals who fabricate hauntings for a living, having never witnessed evidence of the supernatural previously. Still, the cast accurately portrays every character’s sense of unease, which is what matters most.

Shot over ten nights and two days, the majority of the cinematography for Grave Encounters by Tony Mirza fittingly matches the style of stationary and hand-held shots seen in traditional ghost-hunting reality shows, with the fictitious Collingwood Psychiatric Hospital portrayed through the real-world Riverview Hospital, an abandoned mental institution in Coquitlam, British Columbia, built at the turn of the 20th century and closed down in 2012, formerly hosting films such as Watchmen (2009). Grave Encounters utilises this ominous setting remarkably well, presenting the building as a dark, momentous presence to the point where it becomes a character in its own right. The opaque hallways of the abandoned building also greatly lend themselves to the film’s phosphorescently green colour palette as a result of the characters’ dependence on night vision to find their way around.

Similar to other found-footage flicks, Grave Encounters doesn’t possess much of a soundtrack, with the original score by Quynne Craddock only being employed for the deliberately dated, excessively edgy theme for the Grave Encounters intro and the atmospheric track that plays over the end credits, which is suitably bleak and unsettling. In an effort to differentiate itself from those other releases, however, Minihan and Ortiz wanted their spirits to be far less subtle and more forcefully frightening, desiring the various apparitions to “Visibly Run” at the audience as opposed to barely materialising or gradually moving objects.

Outside of its real-world influences, Grave Encounters follows The Blair Witch Project (1999) formula of letting its initially brash characters mentally break down before the incursion of the unnatural, embracing some found-footage clichés, such as slamming doors and slowly opening windows, whilst avoiding others in exchange for more eerie concepts, like when the group learn about the hospital’s disturbing history of lobotomies and medical experimentation. In terms of the spirits’ appearance, each harbours a serviceably sinister, if somewhat generic design, often sprinting towards the camera with a cheesy CG effect that distorts their eyes and mouth, spoiling the horror, much like the film’s frustrating overreliance on camera glitches whenever supernatural frights occur.

In summary, although Grave Encounters starts rather slowly, once the first crew member disappears, the pacing picks up nicely, with plenty of twists, turns and creepy surprises to keep the film rolling along. While hardly original or downright terrifying, Grave Encounters gets almost every beat of its found-footage premise right, succeeding in its attempt to critique the many ghost-hunting reality shows that inspired it, even surpassing its higher-budget, candidly titled 2012 sequel; Grave Encounters 2, a largely forgettable, strangely self-referential expansion to the ghostly frights and low-budget storytelling of the first. Rating: 6/10.